Q&A with Greasepaint Puritan Author Maya Cantu

This guest author post is a Q&A with Maya Cantu, author of the new book Greasepaint Puritan, from the University of Michigan Press. The book is available in hardcover, paperback, and ebook formats.

What made you decide to write about Bradford Ropes? When did you first encounter his works?

Greasepaint Puritan builds upon a long fascination with the work of Bradford Ropes that started with my dissertation (which transformed into my first book, American Cinderellas on the Broadway Musical Stage: Imagining the Working Girl from Irene to Gypsy). In its iconic and more familiar screen and stage versions, 42nd Street is, of course, a Cinderella narrative about chorus girl Peggy Sawyer “going out a youngster and coming back a star” in the musical Pretty Lady. But what struck me about the Ropes novel, by contrast with later adaptations, was the irony with which Ropes frames Peggy’s achievement of the American Dream and the intensely collective focus of his novel; Peggy is only one cog in the complex machine of putting on a show. And I found it to be such a vibrant read, filled with bawdy wisecracks, innuendoes and the “pungent aphorisms of Times Square” (in Ropes’s own words)—some too spicy even for Pre-Code Hollywood! I was really enthralled with the blend of elements in 42nd Street: time-honored backstage tropes—the footlights, the greasepaint, the applause—but also piercing industrial critique, satire of show business shibboleths, and a rich vein of empathy for performers and artists working in a difficult and highly competitive industry. After 42nd Street, I wanted to read more.

This wasn’t terribly easy, as Ropes’s books were entirely out-of-print circa 2010. However, I was fortunate enough to be able to obtain library scans of all three books in what I call Ropes’s “backstage trilogy,” which also includes Stage Mother (1933) and Go Into Your Dance (1934). I realized that 42nd Street was by no means a one-off—and that all three books expressed not only a distinctive stylistic voice, but a consistent thematic focus on the lives and relationships of gay men working on Broadway in the Jazz Age and early Depression. It was frustrating to find so little biographical information available on Ropes—and the book really stems from my desire to change that situation, as much as from my love of his writing.

What challenges were there for a gay man working on Broadway during the 1920s and 30s? What are some challenges Bradford would have faced behind the stage?

Bradford certainly encountered many challenges as a gay man working in vaudeville and on Broadway throughout the 1920s and into the early 1930s—and he chronicles many of these obstacles in the pages of his novels. Even though Broadway was a more permissive industry than many other fields, homophobia still structured many aspects of producing, writing and casting shows. Ropes dramatizes this in his 42nd Street through the contrasting characters of dancer Billy Lawler and chorus boy Jack Winslow (a self-described “great big gorgeous camp” who was cut from the screen and stage versions). In the book, Billy is showman Julian Marsh’s lover—but because Billy is discreet about his sexuality, he is able to land the “juvenile” romantic roles in musical comedies that would not be available to the more flamboyant and unabashed Jack.

Bradford, too, would certainly have observed the censorship laws restricting roles and representation for gay men. The Wales Padlock Law of 1927 gave New York City’s licensing commissioner the ability to revoke a theater’s license if convicted of “obscenity”—which the law often conflated with homosexuality. Wales Padlock famously raided Mae West’s ribald Pleasure Man, arresting West and all 56 members of a cast led by drag queens, on the night of its opening at Broadway’s Biltmore Theatre. And one of the most fascinating discoveries of my research is that Ropes, after rebelling against a “Proper Bostonian” upbringing, started his career in vaudeville dancing in support of a female impersonator named Alyn Mann: a fact he later felt compelled to hide from the press.

But, for all of these challenges, there was also the glittering silver lining of the Pansy Craze, which made queerness visible and fashionable—if still bound up with “nance” stereotypes. Between 1931 and 1934, multiple novels came out featuring positive and nuanced depictions of gay, lesbian, and even occasionally, transgender characters. If Ropes felt pressure to suppress his identity as a gay man onstage, where he danced under the stage name of Billy Bradford, then his backstage novels allowed him a bold new stage to critique these conditions of concealment—and he does so powerfully in 42nd Street, Stage Mother, and Go Into Your Dance.

What surprised you the most when conducting research for this book?

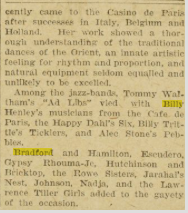

I was very pleasantly surprised to learn definitively that Ropes rubbed shoulders with Ada “Bricktop” Smith (about whom I had previously written for a collected essay in Reframing the Musical: Race, Culture and Identity). In both his novels Stage Mother and Go Into Your Dance, Ropes alludes to characters frequenting Chez Bricktop, the expat African American hostess’s legendary nightclub on the Rue Pigalle. This suggested to me that Ropes, who performed in Paris and Cannes from 1926 to 1927, was personally familiar with Bricktop’s club. But then I found an astonishing piece of archival research. A December 1926 article in the Chicago Tribune and Daily News illuminated how Ropes (as Billy Bradford, and with his dance partner Marian Hamilton) shared the stage at a gala at the Claridge Hotel in Paris with not only Bricktop—but also with the great Grenadian British singer Leslie “Hutch” Hutchinson and with the evening’s headliner: Josephine Baker, whom Ropes also references several times in Go Into Your Dance.

It was gratifying to re-encounter Bricktop in the research process for Greasepaint Puritan. On a deeper level, the discovery underscores how closely Ropes’s career as a dancer and writer was intertwined with the Harlem Renaissance, both in the United States and abroad. I was aware from Ropes’s novels, including 42nd Street, that he was very interested in the tensions of cultural appropriation during the 1920s, from his perspective as a dancer—but the research process also unveiled his working relationships in Europe with Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake, bandleader Sam Wooding, and others. From early on, I knew that Greasepaint Puritan was a story about a Boston-bred Puritan working incongruously on Broadway and interacting with a multiracial culture very different from his upbringing. As the research progressed, Ropes’s encounters with Black artists and artistry became increasingly prominent within this larger narrative.

Which aspects of Bradford Ropes’s life do you think will resonate with readers the most?

Over the course of my research, Bradford Ropes emerged to me as not just a gifted dancer and distinctive writer of backstage fiction—but as an individual who lived his life with an authenticity that I think will resonate with readers of Greasepaint Puritan. On a practical level, it would have been very easy for Ropes—a Mayflower descendant whom I learned had been the president of the Children of the American Revolution of Wollaston, MA—to pursue the path that had been set out for him. He had been “slated for a business career” by his parents after college—but instead, he joined up with a female impersonator in vaudeville and embarked upon a show business career that carried him from the respectable WASP world of “Proper Boston” in the early twentieth century, to the immigrant melting pot of American vaudeville, to the gay London of the Bright Young Things and the Paris of les années folles, to performing on Broadway in musical comedies and revues. And after this varied show business career from 1923 to 1932, Ropes absorbed his experiences into backstage novels so colorful, candid and bawdy that nobody could have believed a Boston Puritan wrote them—unless they know the story of Bradford Ropes!

What do you hope readers will take away from Greasepaint Puritan?

I certainly hope Greasepaint Puritan will inspire readers to seek out more writing by Ropes. 42nd Street and Go Into Your Dance have both been back in print since 2021, but Stage Mother—which is actually my favorite of the books in Ropes’s 1930s backstage trilogy—remains out-of-print and very hard to access. Similarly, with his longtime screenwriting collaborator Val Burton, Ropes wrote a wonderful Boston-set historical novel called Mr. Tilley Takes a Walk (1951) that I would also love to see come back into print. It has elements of his Depression-era novels and a substantive amount of theatrical subject matter, but something of a warmer tone than the earlier work.

More generally, I hope Greasepaint Puritan leads to more consideration of backstage novels and backstage fiction within conversations about both theatrical and literary canons. In Greasepaint Puritan, I write about Ropes in the context of underappreciated 1920s and ‘30s novelists like J.P. McEvoy (Show Girl) and Beth Brown (Applause)—but also within a body of work that includes writers like Sinclair Lewis, Elmer Rice and James Baldwin. As a collective form, backstage novels can be difficult to categorize—yet they illuminate so many contemporary conversations about the theatre industry: from labor inequities, casting and representation, to questioning the myth of “the show must go on” at all costs. I hope Greasepaint Puritan makes the case for Ropes as a major writer within a form that has too often been viewed as minor—and also that his 42nd Street takes its place alongside the iconic adaptations it inspired.